The Declaration of Independence will sell Wednesday at Sotheby’s, with the result — estimated to fall between $2.5 million and $5 million, according to the auction house — sure to make headlines.

After the unavoidable Nic Cage jokes, the inevitable question will surface: “Wait, they're selling ‘the’ Declaration of Independence? Isn’t that in the National Archives?”

Yes and no.

In the world of rare manuscript and document collecting, the Declaration reigns supreme. While prices for the best examples routinely top millions, there are plenty of nuances when it comes to this prestigious corner of historic collecting, especially with respect to the various types and printings of the Declaration.

The document, described by expert authenticator and appraiser of American historic documents Seth Kaller as “the greatest breakup note in history,” was famously born after the Continental Congress adopted it on July 4, 1776.

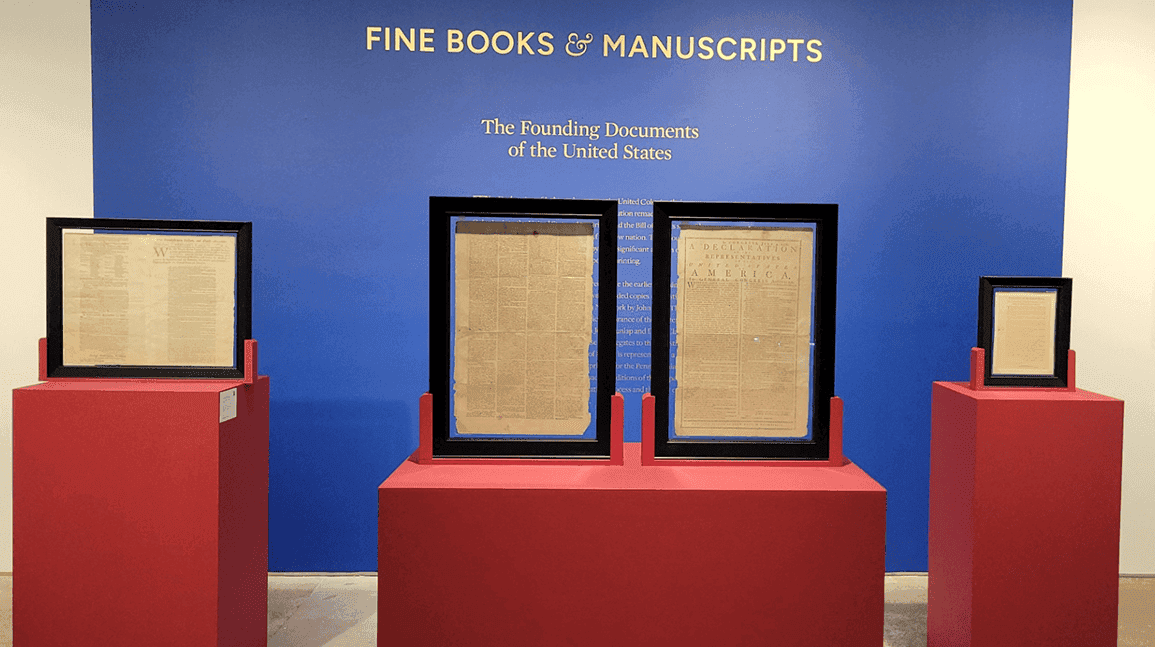

Soon, the first copies of the Declaration were created by Continental Congress printer John Dunlap, who used a manuscript copy to print an estimated 500 to 1,000 copies. This printing, known as the Dunlap Broadside, is the first and most valuable printing. Today, around 26 examples remain extant, with nearly all in public institutions.

“News had to get out that Congress declared independence through (Johannes) Gutenberg's invention — the technology of the printing press — and the greatest significance of the Dunlap is simply that it came first,” Kaller said.

These copies are considered to be nearly unobtainable. Though, in one particularly stunning incident, one man purchased a copy for just $4. The find of the century occurred at a flea market in 1989, when a Pennsylvania man came across a painting set in an old, ornate frame.

Quickly deciding he was more interested in the frame than the art, he paid his $4 and ripped out the painting with the intention of repurposing the frame. Hidden behind the painting he found a folded copy of a Dunlap Broadside. It sold for $2.42 million in 1991 at Sotheby’s. Then, in 2000, it was sold to a group including Norman Lear for $8.14 million. That sale marks the last time one of the coveted Dunlaps sold publicly.

Most often, when we see these million-dollar sales for Declarations at auction, they fall into the next bucket: July 1776 printings, created in various towns in the colonies in the days and weeks after the adoption of the Declaration, using the Dunlap copy as a reference to print more broadsides. These printings were intended for display in places such as the town square and for public reading sessions in order to alert the locals of the dramatic news.

“There is more value closer to the July 4,” Kaller said, explaining the differences in desirability of these rare documents and highlighting the premium attached to those printed earliest.

For reference, the signed and engrossed copy of the Declaration, displayed in the National Archives, was not completed until August.

A July 1776 copy, one of just two examples of the first Massachusetts broadside printing in private hands, sold last year at Heritage for $2.895 million. The copy poised to sell Wednesday at Sotheby’s was printed July 11, making it one of the earliest non-Dunlap printings.

However, unlike typical broadsides, defined by Kaller as “a single printed page with text only on one side,” this copy is a newspaper-broadside hybrid, printed by John Holt in the New-York Journal.

Newspaper copies such as the Holt example are typically less desirable than traditional broadsides, as collectors often prefer the aesthetics of broadside examples, though, as Kaller says, chronology of printing remains the most important element in determining value. He adds the Holt copy, hailing from New York, is far rarer than Massachusetts examples.

Kaller, who claims he became the largest buyer of historic documents over three decades ago and is a renowned expert in the industry, says he has noticed values climb “tremendously” in his years watching the market.

There was a narrative that collectors and overall interest in American history was “dying out” a decade ago, according to Kaller, but due to a number of factors, the demand has returned in droves.

Kaller credits the Broadway show “Hamilton” as well as the “sorry state of our politics” as two elements which helped restore interest in this era of American history in the general public.

Will Stern is a reporter and editor for cllct.