Like Davy Crockett and Wyatt Earp, Johnny Appleseed is among the legends of American folklore whose story is certainly real, though poetic license has been used to expand his legend.

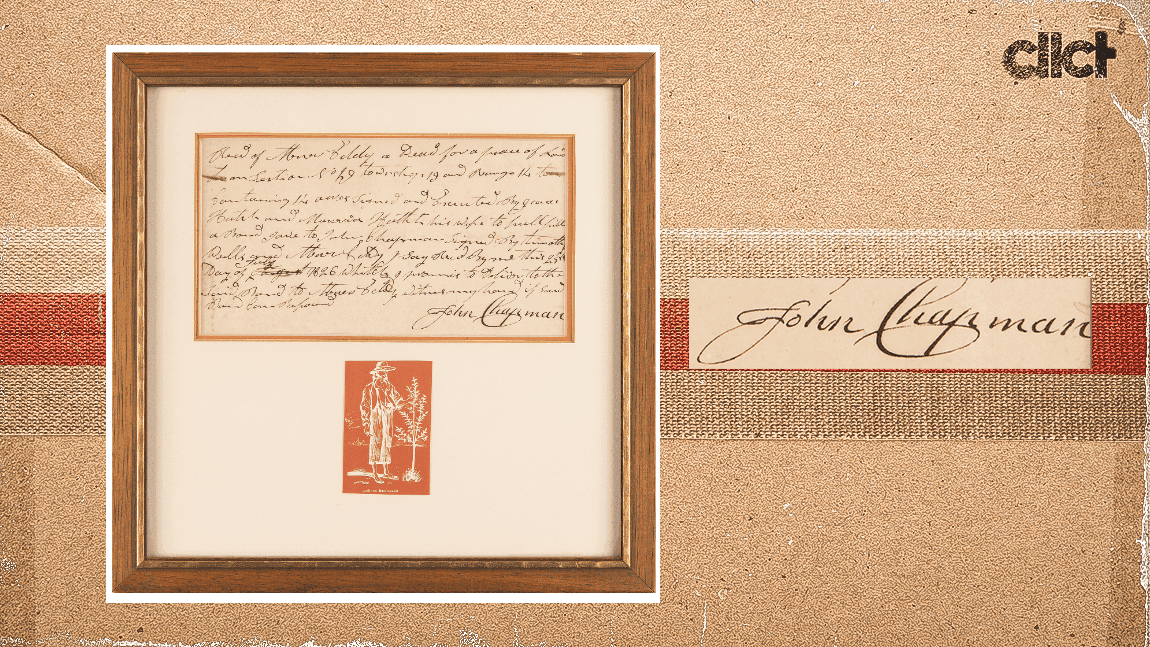

While Appleseed — his real last name was Chapman — did, in fact, spread apple trees across what was then the Northwest, his signature is so rare that an upcoming auction that boasts his autograph is one of just a handful ever seen.

Given its unprecedented nature, RR Auction put an estimate of "$600" on the document. With a week left in the auction, bidding, including buyer's premium, has already topped $6,000.

"There are serious, manuscript collectors bidding on this item. I would think any American completist would have to have John Chapman in their collection," RR's Bobby Livingston said.

PSA chief authenticator Kevin Keating told cllct the current item is the only "Appleseed" autograph he has ever seen. JSA's Jimmy Spence said he has seen one other — sharing an 1822 petition from residents of Mansfield, Pennsylvania, asking for a minister to be ordained to establish a local chapter. That signature, housed in the Swedenborg Library Archives at Bryn Athyn College, matches the Chapman signature of the item being auctioned.

The signature is dated 1826 and gives him the ownership to a 14-acre parcel of land, which shouldn't come as a surprise because Johnny Chapman was actually an early real estate mogul.

Wait, what?

Yes, Johnny Appleseed's life was based on Johnny Chapman, but was heavily exaggerated. Chapman was not well known nationally when he was alive. He died in 1845, and "Johnny Appleseed" first came to life as a character in an 1871 piece in Harper's Monthly. That character was a charitable one, giving away apple seeds out of the goodness of his heart so other people could have immediate sustenance.

A 1950 children's book by Mabel Leigh Hunt came next and a Disney musical, released as a standalone in 1955, followed.

Chapman wasn't so much the person "Johnny Appleseed" was, according to those who researched the real man's life, including Robert Price, author of the 1954 book "Johnny Appleseed: Man and Myth."

He planted apple seeds to hold the land that he bought — some 1,200 acres in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois — and he sold those apple trees, from seeds he picked up for free, for 6.5 cents each.

As pointed out by Sam Kean, author of "The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love and the History of the World," in a podcast, Johnny's apples actually weren't for eating. They were made to make hard cider in an era when Americans were drinking more heavily than any time in our nation's history. By fermenting over the winter, people made Applejack, which involves letting the solution get frozen and then removing the ice. Applejack can get up to 66 proof, Kean noted.

Yes, despite wearing a burlap sack with a cooking pot on his head and living a life on the road, Johnny Chapman was not poor.

This might be one of the reasons why his signature is so hard to find. He never needed to be lent money. In fact, Chapman was known to have strategically buried money often so he could come back and use it later.

The collector who ends up with the autograph will now hold the signature of a shrewd entrepreneur, instead of the beautiful philanthropist that mythology would have us believe.

Darren Rovell is the founder of cllct.com and one of the country's leading reporters on the collectible market. He previously worked for ESPN, CNBC and The Action Network.