A throwaway joke at the beginning of the 1980 movie “Airplane” sees an elderly woman ask a flight attendant for some light reading. She is offered a leaflet of “famous Jewish sports legends.”

It’s played for a quick laugh. One the audience easily understands as a reference to the dearth of Jewish names in the pantheon of athletic greatness.

As a Jewish kid growing up obsessed with the movie more than two decades after its release, I found the joke hilarious — after all, it’s true.

Short of a few proud names (we will be getting to them later), it’s no secret Mickey Mantle, Muhammad Ali, Michael Jordan and Wayne Gretzky were not, in fact, members of the tribe.

Still, I, like most Jewish kids obsessed with sports, grew an uncanny knack for naming just about every active Jewish athlete, particularly baseball players, no matter how meager their contributions on the field.

From Kevin Youkilis to Ryan Braun, Shawn Green to Ike Davis, I kept tabs on all of them.

Why? Because, even now as I see my chances of making it to the big leagues dwindle — it has been about 10 years since I played my last game of high school ball, and I recently pulled a muscle taking out an AC unit — it’s a little reminder the pamphlet of Jewish sports legends continues to grow, regardless of how slowly.

Still, one name, above all others, remains a source of Jewish pride: Sandy Koufax.

The quest begins

When Dr. Seymour Stoll was 8, he began collecting baseball cards. By the time he was about 14, it was 1966, the final year of Koufax’s career. A Jew living in Los Angeles, Stoll pulled a 1966 Topps Koufax card out of a pack from a local drug store.

He already knew who Koufax was — everyone did “unless you lived in a cave.”

Stoll showed it to his father, who remarked not only how great of a ballplayer Koufax was, but specifically, how great of a “Jewish” player the Dodgers pitcher was, certainly helped by his famous decision to refuse to participate in the opening game of the 1965 World Series in observance of Yom Kippur.

“Why don't you collect all of the Jewish players?” suggested Stoll’s father.

Stoll laughed. “How hard could this be? I figured it would take me like a week or a month,” Stoll recently told cllct. “I didn’t realize it would take me 45 to 50 years to complete.”

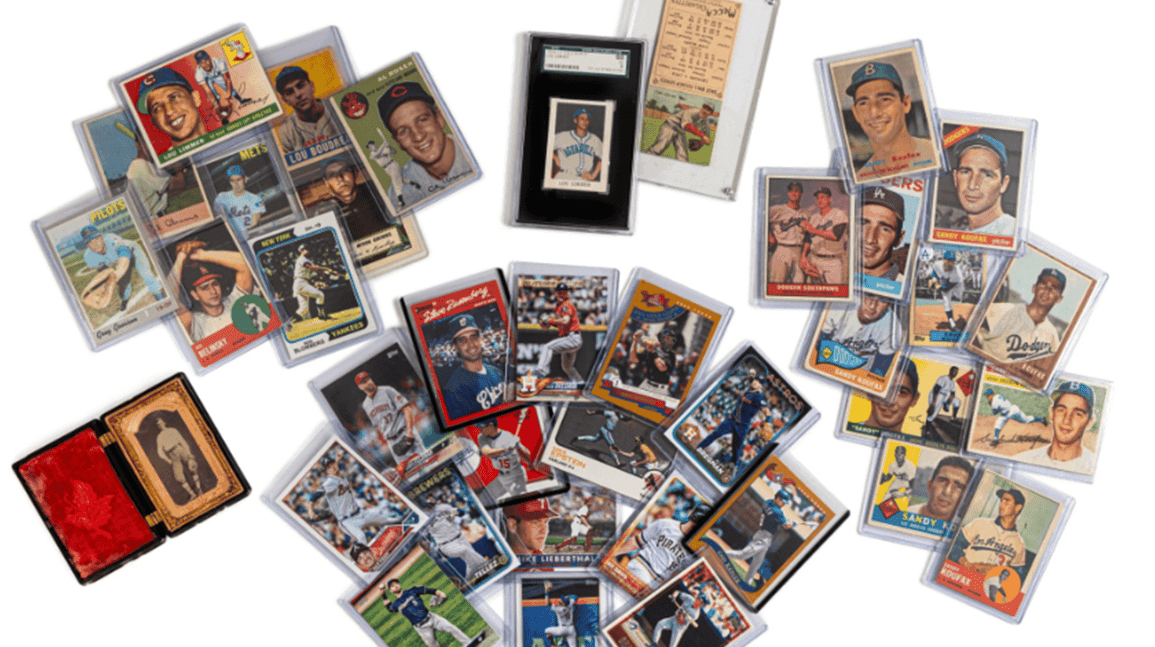

Stoll’s holy collecting quest, which would ultimately result in the accumulation of the most complete collection of Jewish baseball players ever assembled, numbering 506 cards and representing 191 players, commenced.

This week, the collection will be auctioned at Sotheby’s, with a high estimate of $700,000.

“It’s time to pass it on to the next generation," Stoll said. "I’m hoping it ends up being someone who will be a patron of a museum and exhibit the collection the same way I have for these past few years.”

Stoll's quest took nearly a half-century and was filled with more obstacles than he originally anticipated.

There were easy names to track down, such as Koufax and the great slugger Hank Greenberg. Plenty of cards to choose from and plenty of information on their Jewish heritage.

But it was the guys who were relative unknowns, playing in a game or two and fading into the annals of the baseball reference database, who posed the greatest challenge.

Max Rosenfeld played in 42 games from 1931 to 1933, stepping up to the plate less than 60 times and recording just 17 hits in his career. Hardly on par with “The Left Arm of God.”

Rosenfeld didn’t appear in any of the standard American card releases from the era, but, undeterred, Stoll uncovered a 1946 Cuban issue featuring the long-forgotten outfielder.

There are even a few Jewish players in the famed T206 set, including the “Yiddish Curver,” Barney Pelty, one of the first Jews in the American League.

“He was one person who wasn't afraid to let everybody know that he was Jewish,” Stoll said.

Players, fearing antisemitism and blackballing due to their identifiably Jewish names, often would opt to go by a more “American” name, which made Stoll’s job all the more difficult. Undeterred, Stoll utilized Jewish historical societies all over the country, contacted the Baseball Hall of Fame and poured over hours of publicly available records.

Phil Cooney, a third baseman for the Yankees in 1905, played just a single MLB game. But Stoll uncovered that Cooney had actually changed his name from Cohen, much like Sammy Bohne, also formerly a Cohen, who played seven seasons in 1916 and 1921-26. Of course, they had to be included in the collection.

Stoll holds particular admiration for Andy Cohen, who played for the New York Giants under manager John McGraw. Cohen refused to change his name, despite pressure as he started his career in the Texas League. A New York Times article from July 1928 headlined “ANDY COHEN KEEPS HIS NAME” reports Cohen told friends his name was good enough for him.

“To take any other would be an attempt to hide the fact that he was a Jew … it would hurt his mother," the story said.

“The collection tells what the Jews had to go through, all the adversity, to be accepted into not only baseball, but basically the integration of the Jew into American society,” Stoll said.

Collecting the list of nearly 200 Jewish players led Stoll to track down some incredibly rare cards.

An 1867 tintype card of Levi Meyerle, who led the National Association in batting average on two occasions and is considered one of the greats of the 19th century, is secured in the collection — one of just two known to exist.

The other is in the Museum of London, part of their massive collection of vintage baseball cards — a result of their claim baseball is a descendant of British games like Rounders and Cricket.

"It was a labor of love"

The collection, which Stoll completed within the past five years, has been exhibited in more than a dozen museums, including the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, the Detroit Historical Museum in Detroit, the Jewish Museum in Milwaukee and the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles.

According to Stoll, it generated more than $10 million in ticket sales during its tour.

While on display at the National Museum of Jewish History, Stoll visited and was ecstatic to see “all these rabbis in Philadelphia Phillies uniforms.”

“It was a labor of love,” Stoll says of his multi-decade journey. “Money had nothing to do with it. Everyone thought I was crazy. I paid $1.50 for a Koufax card, and they thought I was insane.”

But the connection to his faith — Stoll is a practicing Modern Orthodox Jew — and the collection’s impact on the history of his people is worth more than money can buy. Stoll recalls getting beat up as a kid after school for his religion.

“But once they found out Sandy [Koufax] was a Jew, they figured, well, if he’s Jewish and we like him, then you must be OK. Instead of fighting, we became friends.”

"The most significant archive of its kind ever assembled"

A few weeks ago, in the lead-up to the auction at Sotheby’s, Stoll’s collection was featured in a YouTube video with Rabbi Pini Dunner.

Soon after, Stoll received a call from a woman who was related to the family of Morrie Arnovich, who kept Kosher on the road, despite the obvious difficulties of maintaining a religious diet restriction while playing for an MLB club in the 1930s. They told Stoll that Morrie’s brother was actually considered a better ballplayer and prospect, but refused to play on Shabbat, and therefore never made it to the big leagues.

Though he might be parting with the collection when it sells at Sotheby’s, which says it is “the most significant archive of its kind ever assembled,” the completed challenge handed down by Stoll’s father will forever stand as a testament to baseball’s deep ties to American and Jewish history.

After the collection’s nine-month stint at the Museum of American Jewish History was up and it was time to remove the exhibit, Stoll says employees were crying.

“They didn’t want to take it down. They wanted to keep the exhibit alive.”

Thanks to the years of work and detailed research Stoll recorded in the process of completing this collection, it surely will be kept alive, in one form or another.

Will Stern is a reporter and editor for cllct.