One question immediately comes to mind when viewing the artwork of Graig Kreindler: How is this a painting?

Kreindler brings color — literally — to baseball history through his lifelike oil paintings, taking a black-and-white image of a scene, such as Lou Gehrig’s “Luckiest Man” speech, and using his paint brush like a time machine, transforming the image into full color.

The Brooklyn-based artist has been documenting baseball history on his canvas since 2007, earning the distinction of being one of the great sports artists of our day, with past exhibitions held in the Negro League Baseball Museum among other institutions.

But before he was “The Painter of the National Pastime,” as his personal website describes him, Kreindler was an artistic kid growing up in Rockland County, N.Y.

“I've been drawing, you know, since I was able to hold a pencil,” Kreindler told me on the phone one morning in mid-July while working on his latest commission, a painting of a benefit game for Cleveland Bronchos pitcher Addie Joss.

As Kreindler was growing up, he turned to the world around him for inspiration.

G.I. Joe. Transformers. Thundercats.

One of the earliest drawings he ever remembers creating depicted He-Man.

Then, he discovered his father’s baseball card collection. One thing stood out immediately. A lot of the cards, largely early 1950s Bowman issues, were actually illustrated rather than photographed.

“Someone had actually physically painted something for each card,” Kreindler recalled. “I was kind of aware of that and thought, 'Maybe that’s something I can do.'" Maybe not as a career, but if drawing a picture of Mickey Mantle would get his dad to give him a pat on the head, it was worth it.

As Kreindler grew toward adulthood, his artistry and love of sports went separate ways. He discovered comic books as a teenager and was inspired to enroll at The School of Visual Arts in New York, where he would devote his efforts and talent toward becoming a cover artist for science-fiction books.

Then, one day toward the beginning of his senior year, he had a mini-crisis. He wasn’t finding meaning in the work.

“I think I just came to terms with the fact that sci-fi stuff wasn't pulling on the heartstrings that I thought it should have,” Kreindler said.

During a portfolio class, meant for students to beef up their body of work to submit for work after graduation, the instructor gave an assignment to illustrate a relationship.

“And for whatever reason, the first thing that I thought of was the relationship between a pitcher and a batter,” Kreindler said.

It had been a few years since Kreindler had taken a real interest in baseball, but suddenly he was reinvigorated with his childhood passion.

He made a painting of Mantle for his father for old times sake. The process would shape Kreindler’s career, as he worked to produce the most realistic painting possible. Even back then, he knew there was no margin for error

“I knew baseball fans were super anal,” Kreindler said. “So, everything had to be right. Mantle’s stance had to be right. The ballpark had to be right. Everything had to be right.”

After positive feedback from his class, the young artist began to wonder: “What if there is something to this baseball thing?”

For a few years he continued honing his craft as a side project. He had just graduated from Lehman College with a degree in Art Education, on the cusp of applying for jobs, when he heard from a family friend who happened to be a journalist.

She wanted to write about his story. The piece ended up in the New York Times Sunday Arts section — a career-defining moment for any artist — and suddenly, at 27, Kreindler saw a future as a full-time sports illustrator.

The confidence boost and the elevated profile left him at a crossroads. Stay on the same track and become a teacher, or pursue art full-time.

In May 2007, the same month he graduated, the article was published, and he took the leap.

“I never looked back.”

By now, Kreindler has his process down to a science. The typical project begins with a client approaching him with an idea, often a specific moment or subject — sometimes even based off a specific photograph.

In the case of the current project, Kreindler was asked to paint the Addie Joss Benefit Game, sometimes referred to as the first All-Star Game, from 1911. He found an image himself, licensed it to ensure the owner of the original photograph is properly compensated, then he got to work.

First, Kreindler examined the image. How many players? Who are they? Which ones are sitting and which are standing? What about the crowd?

Then came the research. “I try to recreate the day in my head,” Kreindler explained, describing various details he investigated such as the temperature, time of day and position of the sun. After he was satisfied, notes printed out by his side, the initial drawing began on canvas.

Finally, the painting began — all the while he held the details of the day in mind.

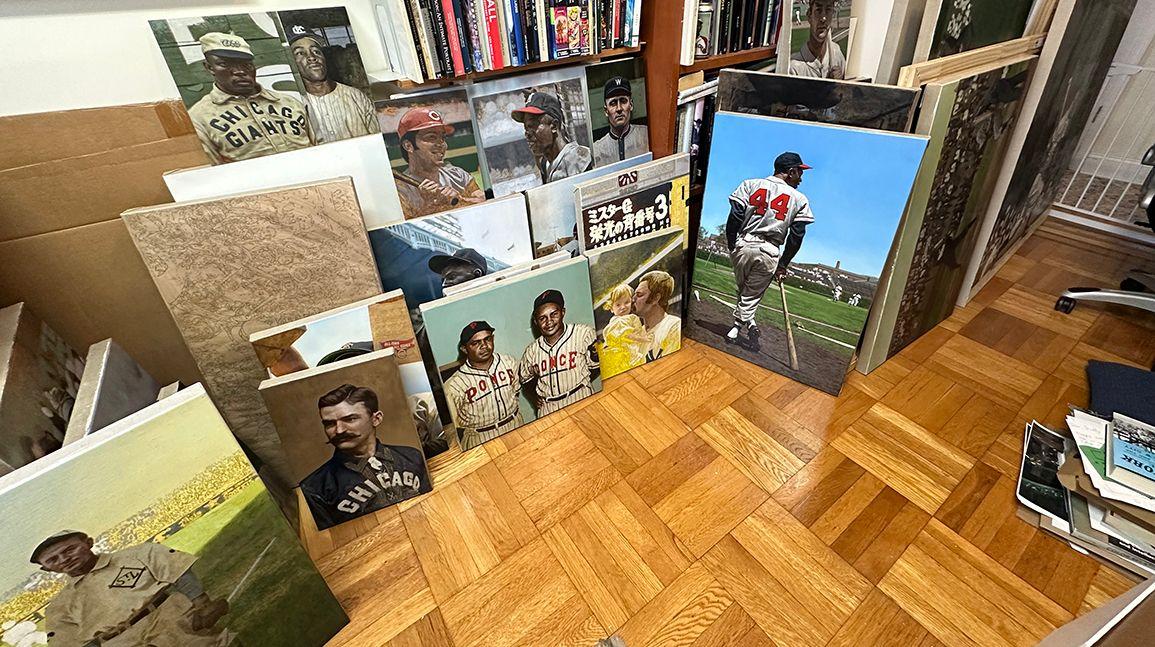

Business is good for Kreindler, and it’s apparent from the look of his home studio (aka spare bedroom), which has canvases cluttering the room in varying states of completion.

A large painting can take years from start to finish, as he jumps from project to project, sometimes to let paint dry, other times to give himself a mental break.

Given the level of perfectionism he holds himself to, it’s unsurprising he needs a break every now and then. His commitment to accuracy results in a tireless quest to nail every detail.

Color can be the biggest challenge. At least, it was back in the day.

Now, Kreindler has it down to a science.

“For me, it comes down to recreating the day,” he said, expounding on the countless questions he asks himself regarding the nuances of the photo — anything from the darkness of a shadow or the definition of a subject provides a clue. Everything plays into the coloring of the painting, down to the amount of cloud cover over the sun.

Today, it’s just another step in the process. He likened it to a translation of sorts.

“The person looking at it needs to be able to kind of hear the crowd and smell the concessions,” Kreindler said of his ultimate goal for a finished work.

That’s not to say all paintings come out perfectly, as he will be the first to admit.

On multiple occasions, Kreindler has found out he made a mistake in a painting — sometimes as long as five years after selling it to the client. But it eats him up inside knowing there’s an imperfect canvas out there with his name on it.

So, he does the unthinkable and calls up the client.

“Hey, I know this sounds crazy, but if I pay for shipping, can you send that painting back to me?” Then the perfectionist will fix whatever detail is nagging him and send it back.

In a recent instance with a Stan Musial painting, it wasn’t even a matter of an inaccuracy. “I could do so much better,” he thought, so he asked for it back and spent a few hours working on it. By the time he was finished, he felt like he had lived up to his word.

Unsurprisingly, considering he has spent 17 years creating these photography-based paintings, Kreindler has a deep respect for photography as an art form, specifically baseball photography from the early 1900s.

“There's something special about about that specific era of baseball photography. I don't know if it's kind of like the perfect confluence of baseball at that time before the end of innocence,” Kreindler said, describing the days before the assassination of President Kennedy which is so often credited as a line in the sand for American culture. “I guess when you have clear photography from the past, I think it's really able to kind of transport the viewer in a way that other stuff can’t.”

Looking through the photographic lens of these time periods, the artist is able to learn a lot. Whether it’s the lack of electronic scoreboards or the crowd’s formal attire, it’s a window into a world where life is different.

“I think that some of the great baseball photography really hits home when I think it has stuff like that,” Kreindler said. “For me, it doesn’t even have to have a star player like Babe Ruth or Lou Gehrig. If it's something that that is able to kind of transport me back to that era, then it’s a successful photograph.”

Since 2007, he’s completed around 350 in his classic style. His smallest works (9x12 inches) retail for $8,600, with anything larger than 16x20 costing $44 per square inch (a recently commissioned piece measuring 38x52 retailed for $86,944).

Though rush fees are offered, the wait list is still incredibly long. As in more than 11 years long.

Kreindler, for his part, knows it sounds wild, but it's simply a testament of the demand for his art.

"Yeah, I'm that backed up," Kreindler said. "Which means I probably should raise my prices again."

All these years later, one line from the 2007 New York Times article sticks out: "If he doesn’t aspire to see his work in art museums, Mr. Kreindler does dream about his art some day hanging on the walls of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y."

Ten years later, that dream came true, after a painting of John McGraw, originally commissioned for a book, landed in the display at the Hall's museum.

“Every painting presents a set of unique challenges, and it's up to me to adapt to them,” Kreindler said. “I want to do a painting that not only the client will like, but that I'm proud of. I’m just always pushing myself, trying to make each painting better than the last.”

Will Stern is a reporter and editor for cllct.