When Jack Hughes was in sixth grade, he underwent a series of skull operations that prevented him from attending school, leaving him at home recovering with very little to do.

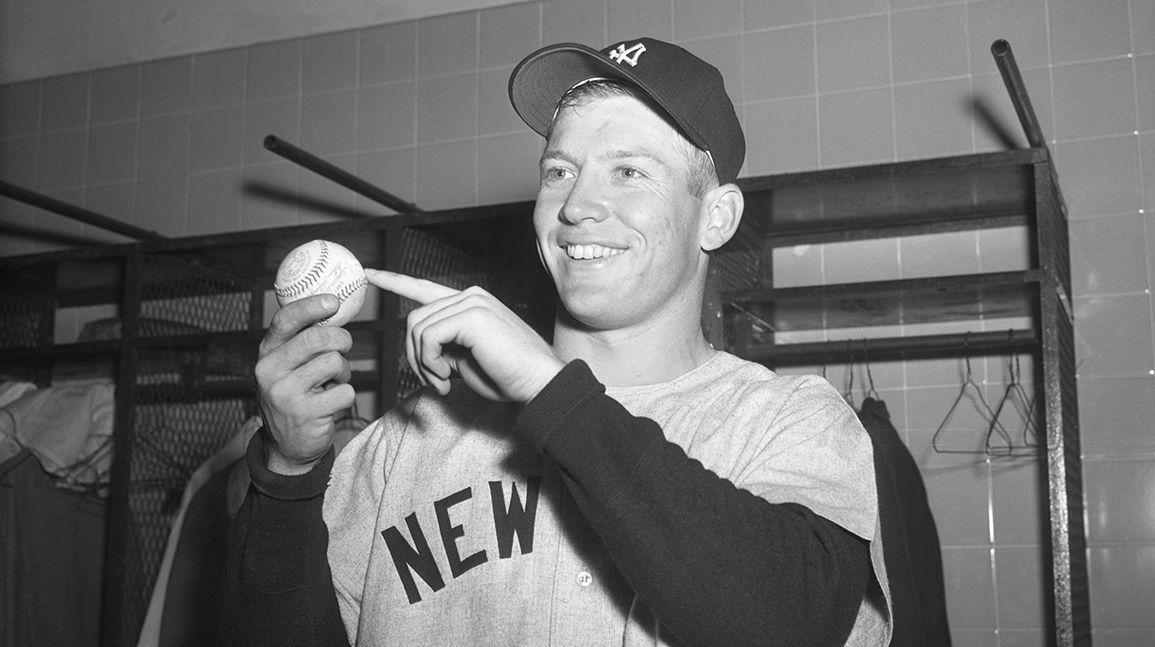

It was 1951 — the same year Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle would make their major-league debuts — and Hughes’ father encouraged him to begin writing to baseball players and asking for their autographs.

The young Hughes was already a fan, but suddenly, the hours spent writing letters and sending them off into the ether — hoping for a reply from his heroes — transformed him into a fanatic.

By the following year, Hughes was back to full health. While he left his hospital visits in the rearview mirror, his baseball fandom was there to stay.

His parents allowed him to visit the hotels where the visiting ballplayers would stay in Washington when they were playing the Senators. There, he’d camp out in hotel lobbies and wait for players to come and go, asking for their autographs. This strategy won him multiple signatures from Ty Cobb, who, along with Mantle, was his biggest hero.

While Cobb, long past his playing days, had earned a reputation as a disagreeable figure, Hughes found the opposite to be true in his encounters with the Hall of Famer.

“Jack was sitting near him outside, and he kept noticing Ty Cobb just was just sitting, waiting. You know, he wasn't going up to him. He was just waiting. And finally, Ty Cobb said, ‘Come over here, boy’,” Hughes widow, Connie, told cllct. “And so Jack went on over, and Jack said all he wanted was a an autograph, and Cobb was really nice, he talked to him about baseball and gave him the autograph.”

Hughes’ adventures collecting autographs and memorabilia from his favorite players only ramped up when he became the Senators’ visiting team bat boy for the 1956 season.

That year, Mantle and the Yankees visited Griffith stadium.

After an at-bat, Hughes picked up Mantle’s bat, and rather than returning it to its normal place in the dugout, he placed it carefully and quietly in the corner, so nobody would see it. Plenty of bat boys regularly pulled similar stunts, but not Hughes. He always made sure to ask the players for their bats. But, in this one instance, he couldn’t resist.

He waited until everyone left, then he snuck it out of the stadium — which coincidentally was also home to one of the longest homers of Mantle's career, a reported 565-foot blast in 1953.

“I think he was afraid to ask Mickey Mantle to sign it. He didn't want to do that because he was afraid that he couldn't keep the bat,” Connie said.

That bat, graded PSA/DNA 9.5, sold Friday at Heritage, where it fetched $384,000 with a pre-sale estimate of $200,000.

Hughes always told his wife when Mantle was inducted into the Hall of Fame, “By god, he was going to be there.”

In 1974, the couple was headed down the Pennsylvania Turnpike for a long-awaited vacation. Jack turned to Connie and asked, “Do you know who's getting inducted in the in a couple of weeks?” He said he was happy to miss it, as there was no place he’d rather be than with her.

Later, Hughes reversed course and decided last-minute that he had to go to the induction — having enjoyed a few weeks with the love of his life. He hopped on a plane to New York, rented a car, and drove up to Cooperstown, where he would take a wrong turn, unfortunately missing the induction after all.

But, as luck would have it, he ended up at the same hotel as Yankees pitcher Whitey Ford. Hughes explained his predicament, though, at that point, it was too late as Mantle had already gone home.

A year later, at Old Timers Day at Yankee Stadium, Hughes was a man on a mission.

Sitting in the stands with his buddies, he told them he was going to find Mantle. They laughed, but Hughes was serious. Hughes ran into the “bowels of the stadium,” bypassing security guards and dashing into a room where he encountered none other than Whitey Ford.

Hughes asked if he remembered him. Ford, whether truthfully or not, said he did, and told him “well, you're in luck. He's just in this next room right around the corner,” escorting him into the room with Mantle, who was surrounded by media.

Ford told the reporters all to stand back and brought Hughes up to his hero, snapping their photo with a disposable Kodak camera.

“He loved, loved, loved, loved, loved baseball, but he also loved the people. I mean, he had all these heroes, and the games meant a lot, but the characters of the baseball players meant more to him,” Connie said.

When Hughes died last July, Connie said she was left with thousands of autographs, memorabilia and cards. The total value was certainly well into the six-figures. But Hughes didn’t care.

“The money meant nothing to him. They could have been worth half a cent, and he just didn’t care about that part,” Connie said. “He never paid one penny for any of his memorabilia.”

Will Stern is a reporter and editor for cllct.